Note to visitors: in that man of the images used on www.leelawrie.com are more than a century old, I have often edited these pictures to make them (1) more visible, and (2) enhanced for easier recognition.

None of these photographs have been distorted to create any “phony” pictures, or alterations that corrupt or distort the originals.

Many of Lawrie’s official photos were taken by Mr. R.V. Smutney, his original documentary-original photographer. None of the photography on this site is altered other than to clarify the images, and make them as reasonably presentable as possible. (None are artificially manipulated to deceive or otherwise inflate them beyond reasonable tweaks.

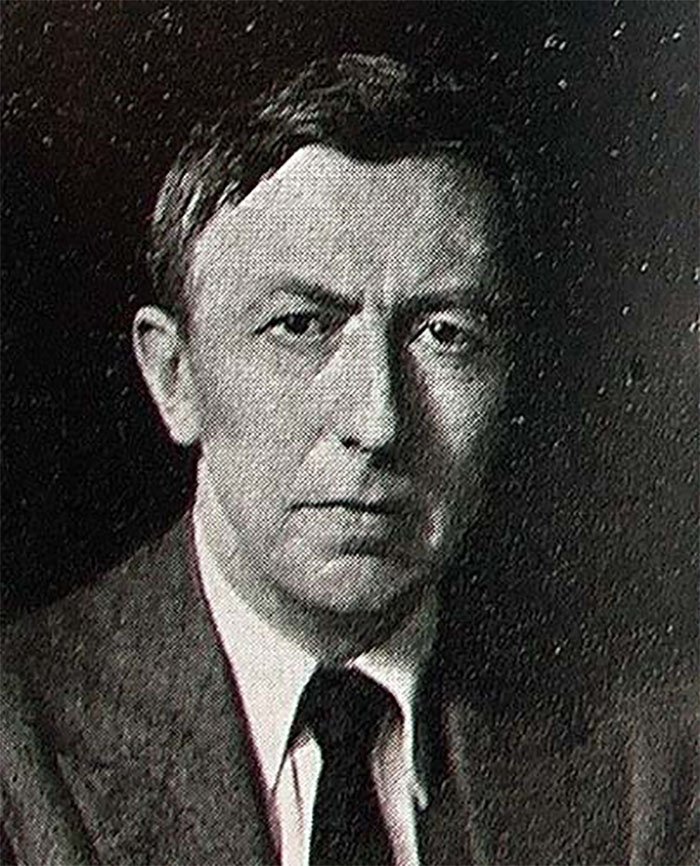

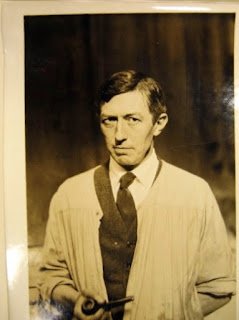

About Lee Lawrie

Youth

Lee Lawrie was born in 1877 in Rixdorf, Prussia. The area is now known Neukölln, one of twelve boroughs of Berlin, in the southeastern part of the city.

In 1881, his mother, Louise Belling, brought him to the United States, sailing from Hamburg to New York on the steamer, Australia, where they arrived that February. This was before the major facility at Ellis Island was built.

After some time in Maryland, Belling brought her son Hugo to Chicago to raise him. She served as a housekeeper and aspired to be a modiste, or fashion designer. But she struggled to raise young Hugo, and she often placed him in orphanages, when she was unable to properly care for him. Eventually, she married a Chicago pharmacist Charles Lowry. At some point after that, young Hugo took the name of Lee Oskar Lawrie, and his mother and the pharmacist two parted. Later in life, in researching his citizenship, he learned that his father, a Civil War veteran, was also a bigamist, and his widow collected his pension.

Like many As was common in the latter days of the 19th Century, Lee left school to work as an adolescent. He worked jobs as a telegraph delivery boy, helped out in a store, and eventually got a job working for a lithographer, and soon developed his talent for drawing. Eventually, he was able to draw ads for beer. He found it amusing that one could actually get paid for something that was enjoyable.

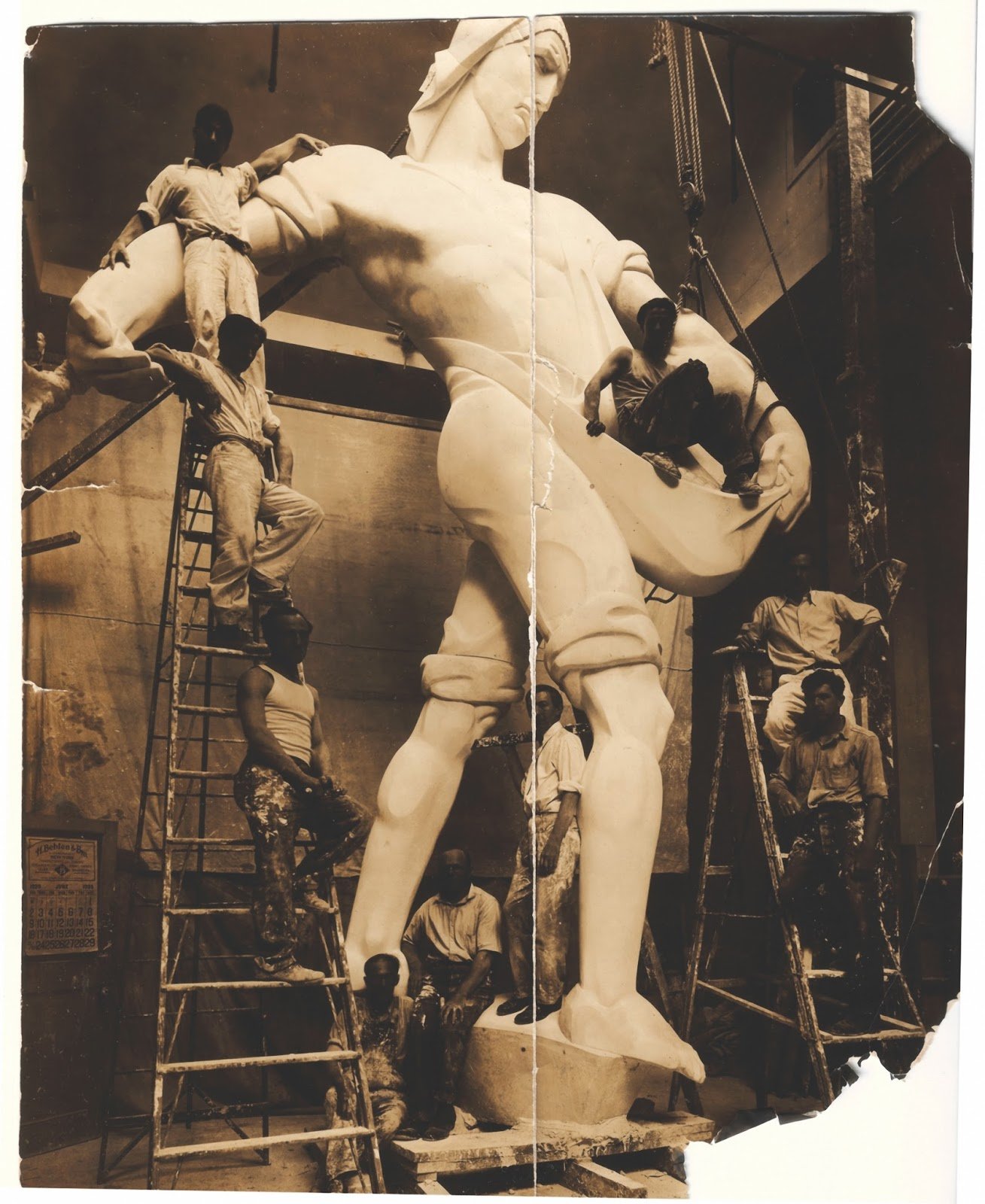

As he approached adolescence, he was always trying to progress with his talent. One day he read a help wanted ad that was titled "Boy Wanted." Of course, this was around 1892-92, when there were no laws that forbade child labor, or discrimination by gender. The ad was seeking a boy to assist in the studios of Henry Richard Park, a fairly prominent Chicago sculptor.

The position was to help build the armatures, or internal "skeletal" structures upon which the sculptures were built. Another major duty of the job was to maintain the clay, by covering it with wet cloth or rags overnight, so that it would retain its moisture, and thereby, its pliability.

During this same period, Lawrie made great strides in learning the art of modeling the clay, and as his skills increased, Park would offer him more opportunities to develop his skills. He lived with the Park family part of this time, and noted that he lived mostly on coffee, bread and cheese, although he was also accepted at the Park's family dining table.

Somewhere around 1892, Chicago began planning for a world's fair, commemorating the 400th anniversary of Columbus discovering America. This became the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition. A great deal of sculpture was required for the fair, and again, Lawrie learned that there was work to be had there. It is also noteworthy that the Exposition brought together many of the world's finest sculptors of the day. Some of the most noteworthy sculptors were Karl Bitter, Daniel Chester French, Gutzon Borglum, and Philip Martiny. Later on, Lawrie would continue his apprenticeship studying under Martiny.

As the work developed, Lawrie managed to find a position as an assistant to Alexander Phimister Proctor, who specialized in Western and Frontier-themed sculpture. Proctor was charged with creating equestrian statuary for the Transportation Building

Lawrie also befriended many other young sculptors, including Andrew O'Connor.

When we examine the life and works of Lee Lawrie, we recognize a genuine Alger Hiss, sort of biography; where a poor immigrant kid from Germany, is brought to America in 1881 by his mother, seeking the American Dream.

But like many American Immigrants, in the 19th Century, (as well as today,) his mother brought him to America at age 4, but she slammed into hard tes, raising him in Chicago during the 1880s and 1890s.

If you recall, Chicago in the 1890s was no paradise. It was the epitome of Darwins concept of Social Darwinism, where the economically strong survived—-and the poor often starved, or died in the streets. It was in these dark urban days that Jane Addams founded Hull House, to provide opportunity for those whose society chose to ignore. For those among you who are curious about Chicago at the end of the 19th Century, check out Upton Sinclair’s bookThe Jungle for an accurate description of what life was like in Chicgao before the advent of the 20th Century.

And if that doesn’t scare you enough, I recommend reading The Devil in the White City, By Erik Larson for additional real and gruesome chunks of nonfiction horror.

Despite the facts that this adolescent Lawrie managed to survive, in the urban nightmare of downtown Chicago in the “Gay nineties,” when Lawrie gained employment creating sculpture for the 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition, it gave him a “trade” and a lifeskill that would serve him the rest of his life.

The Beat Goes On.

By the time the Fair ended, Lawrie had gained enough experience that he gained enough confidence to strike out on his own.

At some point, Lawrie came across the All-Saints church at Ashmont, MA, that had been designed by Cram, Goodhue and Ferguson. In 1895, he moved to the Boston area and ingratiated himself to Bertram Goodhue. He informed Goodhue that he was capable of creating all manners of Liturgical art, that which he could provide for his churches.

At that time, Goodhue was just 26 and Lawrie was merely 18, but the two ended up creating an staggering partnership, that would endure for the next 29 years (until Goodhue died of heart failure.)

In independent declarations later in life, both Goodhue and Lawrie, would assert that in all of Goodhue’s buildings, (with one exception,) all of the sculpture in them had come solely from the hand and mind of Lee Lawrie. (In my research, the sole example of sculpture on a Goodhue building that was not by Lawrie, was the “Museum of Man” in Balboa Park, in San Diego). To the extent of my knowldege, this is a fact.

Goodhue was known to be a chain-smoker (as was your narrator, for 40+ years) and eventually, Goodhue suffered from heart-failure in April 1924 and died at the relatively young age of 54.

To say that this was unfortunate is a grossly understated, especially since ground had only been broken on th Nebraska State Capitol in 1921, and it was a LONG LONG way from being completed. Similarly, Goodhue had projects going with the Los Angeles Public Library, and many other projects going on around the nation.

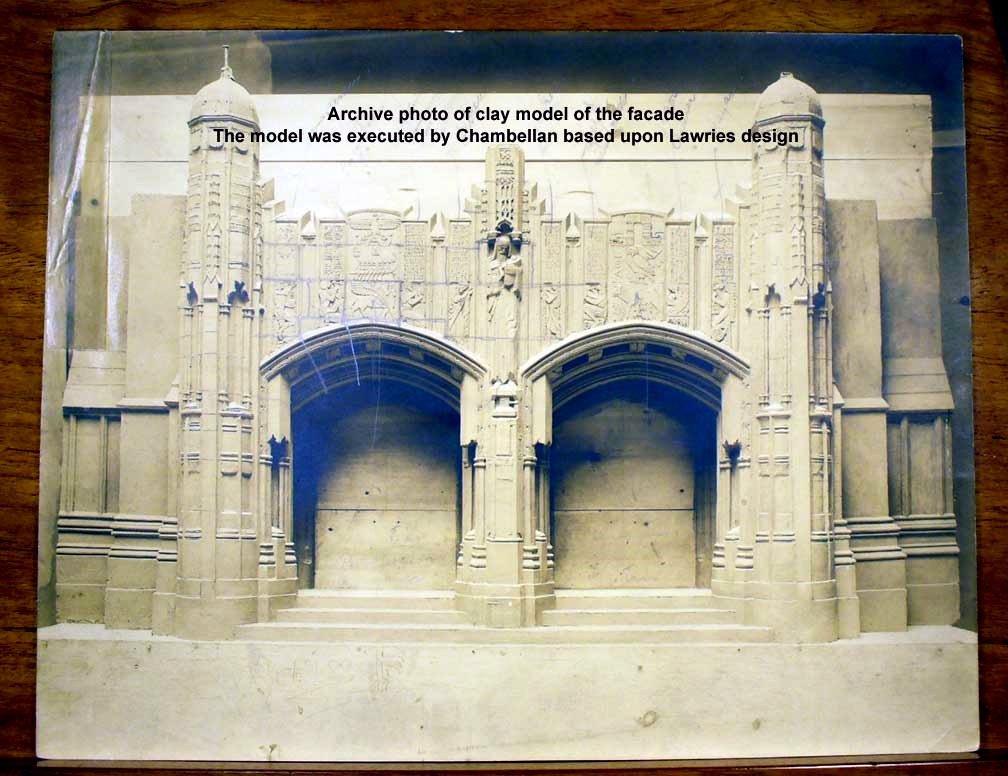

To grasp the magnitude of this loss, imagine what the loss of Steve Jobs was to Apple, and perhaps you will gain an appreciation of the magnitude of a major corporation losing one of its principles is like. Goodhue had earlier designed the Sterling Memorial Library but died before it was completed. The facade of the library was designed by Lee Lawrie, but carved by Rene Chambellan.

THE DECORATION OF THE STERLING MEMORIAL LIBRARY

EXTERIOR

HIGH STREET FAQADE

(Main Entrance, with Reserve Book Room to the left and Linonia and Brothers Library to the right, and, at the Wall Street corner, Exhibition and Rare Book rooms.)

Inscription above the main entrance:

STERLING MEMORIAL LIBRARY

The main entrance is symbolic of the ancient civiliza- tions, based upon written records. The sketch model was made by Mr. Lee Lawrie, of New York City, while Mr. Rene P. Chambellan followed this sketch in his own way in doing the full size sculpture. The doorway is divided into two parts by a figure of a Mediaeval Scholar, the central panel over the left door representing the more ancient civi- lizations: the symbol of Egypt, the Phoenician ship, and the winged bull of Babylon. On each side of this central panel are two panels with Cro-Magnon, Egyptian, Babylonian, and Hebrew inscriptions, with typical scribes below. Identi- fications and translations of these inscriptions are as follows:

Cro-Magnon.

i. Wall engraving of a bison and horse from Les Combarelles. Second phase. Aurignacian epoch.

2. Wounded bison and claviform signs in the Cavern of Pindal.

3. Engraving on a mass of stalagmite in the Cave of La Mairie at Tey-

jat, Dordogne, France. Third phase. Magdalenian epoch.

THE DECORATION OF THE STERLING MEMORIAL LIBRARY

MUCH symbolical and illustrative ornament is found in the Sterling Memorial Library, and we give here a sum- mary of the decoration.

EXTERIOR

HIGH STREET FACADE (Main Entrance, with Reserve Book Room to the left and Linonia and Brothers Library to the right, and, at the Wall Street corner, Exhibition

and Rare Book rooms.)

Inscription above the main entrance:

STERLING MEMORIAL LIBRARY

The main entrance is symbolic of the ancient civiliza- tions, based upon written records. The sketch model was made by Mr. Lee Lawrie, of New York City, while Mr. Rene P. Chambellan followed this sketch in his own way in doing the full size sculpture. The doorway is divided into two parts by a figure of a Mediaeval Scholar, the central panel over the left door representing the more ancient civi- lizations: the symbol of Egypt, the Phoenician ship, and the winged bull of Babylon. On each side of this central panel are two panels with Cro-Magnon, Egyptian, Babylonian, and Hebrew inscriptions, with typical scribes below. Identi fications and translations of these inscriptions are as follows:

Cro-Magnon.

i. Wall engraving of a bison and horse from Les Combarelles. Second phase. Aurignacian epoch.

2. Wounded bison and claviform signs in the Cavern of Pindal.

3. Engraving on a mass of stalagmite in the Cave of La Mairie at Teyjat, Dordogne, France. Third phase. Magdalenian epoch.